Looking at large enterprises in the right way

An enterprise is a multidimensional economic reality that needs to be defined and studied statistically with rigour and clarity. The subject will be different depending on the issues to be analysed. It may be relevant to work at the level of the units defined in legal terms in the Sirene directory (establishment, legal unit) or at a unit level which has more economic meaning, such as the ‘enterprise’ within the meaning of the Law on the Modernisation of the Economy (LME), a concept which first appeared in the 1990s.

The emergence of large groups and their crucial place in the economy have accelerated the need to introduce this new concept of an enterprise into European and French statistics. Its inclusion has had a significant impact on how we see the French economy.

Establishing this method of analysis requires individual monitoring of the most important groups because of their complexity and their contribution to national and international indicators, in particular with a view to identifying the outline or profile of individual enterprises within these large groups. A fine and detailed analysis of the internal flows within large multinational groups, whether domestic or international flows, is essential for the quality of the data and the understanding of French and European statistics.

Enterprise: one word, several meanings

The word ‘enterprise’ is frequently used and covers several meanings. In the broadest sense, it refers to a relatively long-term, complex project in which individuals are engaged. More concretely, it is the structure put in place to carry out an economic activity. In the statistics, the idea of an enterprise has, for a long time, been associated with its legal definition, i.e. a legal unit entered in the Sirene directory of INSEE, defined as a legally autonomous economic unit whose main function is to produce goods or services for the market.

Every day in France, several thousand project owners set up an enterprise: more than a million enterprises were set up in 2022. In order to do so, various legal steps can be taken to frame the project and create the enterprise. Enterprises are born, they live and finally die, so the legal concept of an enterprise lends itself well to demographic analysis. But the daily news also reports on major restructuring events, whether they concern large retail or automotive groups, or the media. In these cases, focusing solely on the individual legal units is insufficient, because the main actors are the groups.

Indeed, economic life is not limited to the creation, development and death of the elementary building blocks which legal units are. Developing an enterprise is not only about growing each of these building blocks, but also about creating new ones and organising them so as to build the desired structure. Groups are formed and evolve, with the legal units being held together by financial connections. Decision-makers in these groups carry out financial transactions involving purchases, sales, mergers, etc. with the aim of building a network of parent-subsidiary links between legal units through equity investments, and improving the economic and financial performance of the group. Within a group, more or less specialised legal units work for each other towards the same ultimate goal, exchanging the necessary goods and services.

This leads to a distinction between internal growth and external growth. Each legal unit can increase its market and financial performance as part of an internal growth process. The parent legal unit of a group may also achieve external growth by purchasing another unit for vertical integration (e.g. buying a supplier of a good or service used in its own production), or horizontal integration (buying another competing unit producing the same output), without affecting the legal independence of each unit.

Taking into account groups of enterprises – an imperative

Groups weigh heavily in the economy. In 2020, the 159 200 groups in France accounted for three quarters of full-time equivalent jobs and value added in the field of non-financial and non-agricultural enterprises, the traditional field for business statistics. The field is very heterogeneous, ranging from 93 700 small groups of just 2 legal units up to 250 groups with more than 100 legal units. The development of groups means that a statistical approach based only on legal units is not enough, because, even if these groups do not have their own legal existence per se, it is at group level that economic decisions are taken, the effects of which ripple through the network of legal units. Given the position and role of these groups, they are themselves equivalent to enterprises, requiring statistical monitoring in the same way as the legal units that make them up. Thus, the definition of an enterprise in the economic sense emerged in the 1993 European Regulation and the 2008 Law on the Modernisation of the Economy (LME): ‘An enterprise is the smallest combination of legal units making up an organisational unit producing goods or services, which benefits from a certain degree of decision-making autonomy, especially in the allocation of its current resources.’

In order to explain the existence of enterprises, their size and organisation, the economic literature refers to transaction costs external to organisations and the costs of coordination within organisations. Depending on the size and organisation of the company, some costs prevail over other costs. Therefore decision-makers size and structure their enterprises by balancing these costs, weighing up one against the other. In this context, collecting legal units together in groups is an arrangement which combines advantages of a large size (economies of scale for production, access to a larger share of the market, etc.) and small size (greater responsiveness, less burdensome regulation, etc.). In the context of globalisation, having a network of small units geared to the host country is another advantage. However, it must be remembered that 85% of the groups present in France are French only.

For users of statistics, information on whether units belong to a group is important. For example, public decision-makers in the regions may be interested in targeting regional small and medium-sized enterprises rather than large enterprises. In order to do so, they need to know to which type of enterprise the legal units in their territory belong.

‘Economic enterprises’, at the heart of the statistics

A major innovation in the European and French statistical system has been the use of an ‘economic enterprise’ as the main statistical unit. Since 2019 (publication of the statistical data for the year 2017), INSEE has been publishing business statistics based on economic enterprises. A distinction is now made between two types of legal units, those outside a group, and those within the structure of a group. The former are enterprises in their own right because they are autonomous, whereas the latter are not, but are included in the enterprise, which the group to which they belong forms.

Compiling statistics on economic enterprises is complicated by the fact that the majority of the administrative information (from tax forms) is available at the level of legal units. It is therefore necessary to aggregate and consolidate this information in order to arrive at statistics at the level of enterprises. And the impact on sectoral and global aggregates, such as the turnover and added value generated, is far from neutral. With the new economic enterprise as the new approach, the picture of the productive fabric is quite different. It appears more concentrated, with a greater contribution from large enterprises. The weight of industry in the French economy increases, all other things being equal, from 25% to 28% in terms of the share of value added contributed by non-financial and non-agricultural enterprises (the latter representing 52% of total value added in the economy), to the detriment of retail and, above all, services. Industry thus measured accounts for 13% of GDP.

Sectoral reallocation and consolidation operations take place. By way of illustration, if an enterprise consists of a legal unit producing and selling chairs and another producing wood intended entirely for the former, the activity of the enterprise is recorded as the production of chairs, even though the two legal units contribute to the timber production sector and the chair sector respectively. However, if things are considered at enterprise level, there is a sectoral reallocation, from timber production to chair production in the statistics.

There is also consolidation at accounting level, that is to say the sale of wood from the former to the second and the reciprocal purchase are subtracted from one another and therefore cancel each other out. Why is this done? There is a convention that internal transactions within the same unit cancel each other out. Otherwise, you could go on detailing internal transactions ad infinitum. For example, within the legal unit producing the timber, exchanges between the wood cutting plant and the wood treatment plant could be recorded, resulting in additional sales/purchases of raw and treated wood. By looking at things at the level of the group, everything happens as if the wood and chair production were vertically integrated within a single entity. However, the multiplication of purchases and sales does not affect the level of value added measured by the difference between production and intermediate consumption, or between sales and purchases.

Another reason for such transactions to be disregarded is that they are recorded at so-called transfer prices that may differ from market prices due to the absence of equivalent transactions in the market.

Very large groups and enterprises with a complex organisation and an international dimension…

The largest groups are complex entities that can comprise several hundred legal units, each specialising in productive, commercial or auxiliary functions. Many of these large groups are characterised by significant exchanges between their subsidiaries as well as with the parent units. Their contours change over the course of restructuring, which raises the question of the continuity of their individual existence in the statistics: once A and B have merged, is the resulting unit still A, or B, or even C? To answer this question, several criteria are taken into account: the respective size of A and B in the initial situation, the identity of the parent unit in the final situation (was it originally the parent unit of A or B?), the share of each entity’s workforce in the initial and final situation, etc.

The largest groups appear to be composites and some include several enterprises. Within these groups there are segments ‘with a certain degree of decision-making autonomy’. For example, LVMH is deemed to be a group in which the different brands constitute relatively independent enterprises, i.e. eight enterprises within the group. In the Airbus industrial group, there are three enterprises reflecting the three segments of civil aviation, helicopters and defence/space.

Illustration 1 – Airbus and its operating segments

In France, there are around 270 large enterprises in the economic sense, generating one third of the added value and turnover of all non-financial and non-agricultural enterprises at national level. According to the definition used in France, these are enterprises meeting at least one of the following two conditions: at least 5 000 employees; more than EUR 1.5 billion in turnover and more than EUR 2 billion in balance sheet total. With a few exceptions, they are French or foreign multinationals based in many countries. In order to grow internationally, they set up there to gain easier access to the internal market, to benefit from lower production costs, to reduce their taxes, etc. In fiscal matters, this is particularly the case for the most complex multinationals.

Although INSEE’s role is ultimately the production of national statistics, it is essential to understand the international dimension of businesses. Large global enterprises have a value chain that crosses borders. The measurement of the wealth created in each country depends directly on the location of the added value created by the legal units. For example, it is interesting to know how pricing is organised in a multinational company. If billing to customers throughout the world is centralised in a single country, this may affect the distribution of the multinational’s turnover between countries according to the amounts paid to business units of the enterprise located in other countries by the billing unit.

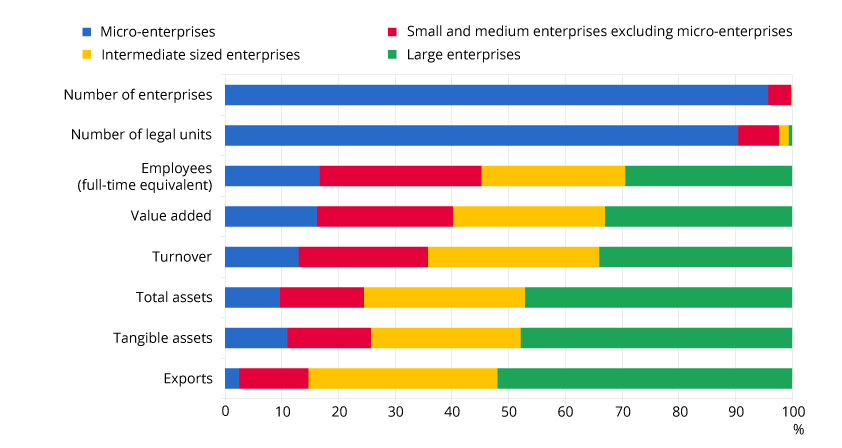

Illustration 2 – Breakdown of various aggregates by enterprise category in 2020

Reading: Large enterprises produce 33 % of value added in 2020. Micro-enterprises (MIC) concentrate 96 % of employees in enterprises.

Coverage: Enterprises of non financial and non agricultural sectors.

Source: Insee, Esane2020.

… make individual monitoring essential

In order to optimise the statistics on these 270 large enterprises which make a significant contribution to the national aggregates, INSEE currently selects some sixty groups, comprising around a hundred of these large enterprises, considered to be the most important and complex, to monitor them individually. These hundred or so enterprises account for about half of the economic weight of the 270 large enterprises operating in France. A team of INSEE experts establishes regular contacts with the relevant departments (accounting, consolidation) of these groups in order to obtain the best possible understanding of their corporate organisation, operation and restructuring. These experts approach the enterprise’s accounts from the point of view of producing national and international statistics. They are also profilers in that part of their work consists of defining, within these large groups, the outline or profile of enterprises in the economic sense. Individually monitored groups provide INSEE with information on their organisation and on internal flows characteristic of their operation, for statistical purposes only and under conditions of statistical confidentiality.

These ad hoc exchanges firstly make it possible to identify enterprises within a group. The segmentation decision is taken by INSEE, usually in agreement with the group, with the aim of best adhering to its governance and the resulting information system, in order to compile statistics at the level of each enterprise. Of the 60 groups monitored individually, 40 are single enterprises and 20 are divided into 2 enterprises or more, such as LVMH and Airbus referred to above.

They also allow the consolidation of accounts on the basis of intercompany flows (i.e. internal transactions which cancel each other out, as in the example of the chairs and the wood) to be calculated and provided by the groups. The sales consolidation rate varies greatly from one enterprise to another. For example, it is higher in automotive and grocery retail groups due to successive sale and resale flows between productive and commercial units and between national and regional purchasing centres.

As for all the many smaller groups, they are treated automatically via algorithms, assuming that there is only one enterprise in each group and by assuming internal purchases/sales between legal units on the basis of their sector of activity (e.g. a chair producer who buys timber from the timber producer).

Overall, concentrating expertise on very large groups makes it possible to improve the quality and meaning of the national statistics by looking at significant economic exchanges within the groups (to which goods or services exactly do they relate? between which legal units? etc.).

This work makes even more sense if carried out at an international level. Under the aegis of Eurostat, the national statistical institutes participate in European profiling work. These joint efforts feed the European directory of groups and enterprises, which aims to become the backbone of European business statistics. The European directory defines the population of groups and enterprises and links the national directories together. Our understanding of transnational enterprises, which is of course more relevant at European level, is enriched by collaboration between the European statistical institutes and the resulting cross-observations. ■

Additionnal information

- Coase R. H., 1937, « The nature of the firm », Economica journal Vol. 4 Issue 16, LSE, novembre

- Dussud F.-X., 2021, « L’entreprise : un concept économique plutôt qu’une définition juridique », le Blog de l’Insee, décembre

- Eurostat, 2023, « Structure of multinational enterprise groups in the EU (source EGR) », Statistics explained, avril

- Francois M. et Vicard V., « Seules les multinationales suffisamment complexes font de l’évitement fiscal », la Lettre du CEPII, N° 434, février

- Insee, 2023, « L’essentiel sur… la mondialisation », septembre

- Insee, 2023, « L’Essentiel sur… les entreprises », juin

- Insee, 2019, « Les entreprises en France », Édition 2019, Insee Références, décembre

- Insee, 2019, « Le profilage à l’Insee », Courrier des statistiques n° 2, juin

- Veltz P., 1996, « Mondialisation, villes et territoires – L’économie d’archipel », collection Quadrige, Presses universitaires de France